- Home

- Julian Leatherdale

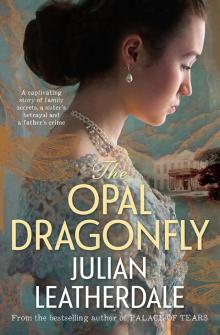

The Opal Dragonfly

The Opal Dragonfly Read online

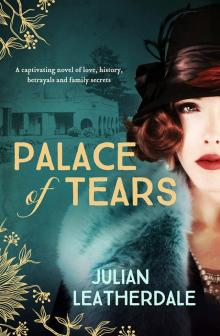

Praise for

PALACE OF TEARS

‘A wonderful historical novel…The Blue Mountains is a place ripe for fiction, iridescently spooky and timeless.’ —Sydney Morning Herald

‘A rollicking, epic tale.’ —Adelaide Advertiser

‘A tap-dancing debut novel, beautifully and lyrically written.’ —Australian Women’s Weekly

‘Passionate palatial page-turner…a Gothic fiction masterpiece.’ —Tasmanian Times

‘This big, sprawling saga…brings together the sophistication of global modernity and the Australian bush, and combines the glitter and glamour of consumer culture with the homeliness of a small regional community.’ —Newtown Review of Books

‘An entertaining, colourful and informative novel…Leatherdale brings to life the grandeur and flamboyance of the pre-war and post-war eras.’ —Write Note Reviews

Julian Leatherdale’s first love was theatre. On graduation, he wrote lyrics for four satirical cabarets and a two-act musical. He discovered a passion for popular history as a staff writer, researcher and photo editor for Time-Life’s Australians At War series. He later researched and co-wrote two Film Australia-ABC documentaries Return to Sandakan and The Forgotten Force and was an image researcher at the State Library of New South Wales. He was the public relations manager for a hotel school in the Blue Mountains, where he lives with his wife and two children. The bestselling Palace of Tears (2015) was his first novel.

www.julianleatherdale.com

First published in 2018

Copyright © Julian Leatherdale 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 76029 307 9

eISBN 978 1 76063 557 2

Typeset by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Cover images: © Lee Avison / Trevillion Images, iStock, dragonfly illustration by Caitlin Hazelquist, Elizabeth Bay House courtesy of Sydney Living Museums

For my daughter

This book is a work of fiction but has its roots in historical research. In the service of fiction, I have taken some liberties with real events, dates, poems and journal entries. For those readers who are interested, I explain this adaptation of historical sources in detail in notes at the back. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this book portrays and names deceased Aboriginal people.

Her poor mother now did not look so very unworthy of being Lady Bertram’s sister as she was but too apt to look. It often grieved her to the heart—to think of the contrast between them—to think that where nature had made so little difference, circumstances should have made so much, and that her mother, as handsome as Lady Bertram, and some years her junior, should have an appearance so much more worn and faded, so comfortless, so slatternly, so shabby.

JANE AUSTEN, MANSFIELD PARK

An example and chastisement to the debased populace of Sydney Town.

GOVERNOR RALPH DARLING ON HIS

NEW SYDNEY SUBURB OF Darlinghurst

And the sunny water frothing round the liners black and red, And the coastal schooners working by the loom of Bradley’s Head; And the whistles and the sirens that re-echo far and wide—All the life and light and beauty that belong to Sydney-Side.

HENRY LAWSON, ‘SYDNEY-SIDE’

An opal-hearted country,

A wilful, lavish land—

All you who have not loved her,

You will not understand—

DOROTHEA MACKELLAR, ‘MY COUNTRY’

CONTENTS

ISOBEL 27 SEPTEMBER 1851

CHAPTER 1 LANE’S TELESCOPIC VIEW

CHAPTER 2 TIME TO GO

CHAPTER 3 LACHLAN SWAMPS

CHAPTER 4 THE SECOND SHOT

ISOBEL 1838 TO 1849

CHAPTER 5 A BIRTHDAY PICNIC

CHAPTER 6 GRANGEMOUTH

CHAPTER 7 BALLANDELLA

CHAPTER 8 THE LOVE TOKEN

CHAPTER 9 A MOTHER’S LOVE

ISOBEL SEPTEMBER 1851 TO JULY 1853

CHAPTER 10 A MATTER OF HONOUR

CHAPTER 11 THE INTERVIEW

CHAPTER 12 A LAST WALK IN THE GARDEN

CHAPTER 13 UNEXPECTED VISITORS

CHAPTER 14 SYDNEY TOWN

CHAPTER 15 THE LETTER FROM ALICE

CHAPTER 16 WATSONS BAY

CHAPTER 17 SINKING

CHAPTER 18 JUNIPER HALL

CHAPTER 19 THE ARTIST

CHAPTER 20 GOOD WORKS

CHAPTER 21 THE ROCKS

CHAPTER 22 CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER 23 THE BAZAAR

CHAPTER 24 WEDDING PLANS

CHAPTER 25 SECRETS

CHAPTER 26 LOVE

CHAPTER 27 LETTERS FROM ABROAD

CHAPTER 28 DUST STORM

CHAPTER 29 GRACE AND AUGUSTUS

CHAPTER 30 THE RETURN

CHAPTER 31 SHAME

CHAPTER 32 EXILE

CHAPTER 33 FATE

CHAPTER 34 MARRIAGE

CHAPTER 35 SECRETS

CHAPTER 36 FORGIVENESS

CHAPTER 37 EXECUTION

CHAPTER 38 THE TRUTH

WINNIE

CHAPTER 39 THE DRAGONFLY LADY

CHAPTER 40 DREAMS

CHAPTER 41 ENDINGS

SOURCES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ISOBEL

27 SEPTEMBER 1851

Chapter 1

LANE’S TELESCOPIC VIEW

Isobel slept badly.

Again and again she startled awake, staring at her moon-drenched room as if she had never laid eyes on it before. She could hear the familiar chimes of the library clock downstairs and the groans of her wardrobe close by but something was not right. Her bed floated, rocking from side to side in the darkness. Or was it the whole house that had slid into the harbour and drifted out to the Heads on the tide?

Isobel’s head nodded again but sleep offered no refuge as she was instantly pulled back under the dark waters of a nightmare. This time she was alone on a beach. Rain fell in torrents from a storm-bruised sky and the ocean seethed, grey and white-capped. Above the din, Isobel could make out a man’s voice, carried on the wind. Help! Please God! Help me! Blinded by rain, she stumbled along the beach, calling in response.

But the drowning man was nowhere to be seen.

She listened to his pleas grow weaker, more desperate. Please God! Help me, please! At last there was only the roaring of the wind and waves. He was gone. Isobel fell to her knees and wept, convinced she could have saved the man if only she had tried harder. And then the scene began again, repeating in an endless loop.

It was a long night. Adrift on her bed, Isobel thrashed about like a swimmer herself in a choppy sea. She felt the drag of the bedclothes twisted round her limbs. Her moans grew so loud it was a wonder they did not wake her sisters next door.

Miss Isob

el Clara Macleod, youngest of the seven children of Major Sir Angus Hutton Macleod, Surveyor-General of the colony of New South Wales, had the singular misfortune to know that at seven o’clock that morning her father was going to die.

To make matters worse, she suspected that half of Sydney knew it too. Isobel understood better than most the impossibility of keeping anything secret in this town. A permanent cloud of gossip hung over the place. Scandals could be whipped up as easily as dust devils on the street in summer. As one of the colony’s most senior public officials, her father was not frightened of the town gossip or even the vile scribblings in The Monitor or Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer.

Isobel’s father was not frightened of anything.

She woke again to hear the chimes from the library. This time they were answered by five bright pings from the mantel clock in her father’s dressing-room. Surely he would be out of bed by now, assuming he had slept at all. What man sleeps peacefully on the eve of his own destruction? Not even her father was that stoic.

Out of habit, Isobel unlaced her nightcap, tucked it under her pillow and straightened her blankets and bolsters. She pulled back the curtains that enclosed her narrow four-poster and looked out the window. The moon hung low in the pre-dawn sky, as small and pale as a pearl. Its extravagant show of glitter on the black water hours earlier had died down to a few sparks. Isobel had loved this view since she was ten but this morning it provided none of its usual solace or pleasure. She was haunted instead by the image of her father in his dressing-room next door, paused halfway through unbuttoning his nightshirt or bent over his washstand, looking at this same moon for the last time.

When the Major moved his family to Rosemount Hall seven years ago, Isobel had shared this room overlooking Elizabeth Bay with her two middle sisters, Grace and Anna. This arrangement had been her parents’ choice and not one Isobel favoured though she bore it stoically. While she had been close to her two sisters when she was small, relations with them had soured over the years; the best she could hope for was to be ignored and spared their cruel taunts. Her only comfort in this cramped front room was falling asleep to the distant lullaby of the waves and waking to a room filled with the dazzle of morning light off the harbour and the prospect of a day’s beachcombing along the bay or an amble in Rosemount’s gardens. Or, if she was lucky, there would be a picnic outing on a beach with Mama.

There had been many changes since those early days. Two years ago, Isobel’s eldest sister, Alice, had married and moved to England with her new husband. In January of the following year, Sir Angus’s youngest son, Richard, was killed in a horse riding accident on the family farm at Camden. And then, just over a year ago, their blessed mama, Winnie, had died of dysentery. Isobel’s favourite brother, William, now lived out of town but kept a room at Rosemount where he came and went as he pleased, unlike Joseph, whose long-running quarrel with Father had led to his banishment.

Rosemount was not the same. Sir Angus still had callers and entertained close friends but, with so many departures and absences, the great house felt half-empty. Several of its rooms were permanently closed up. The Major lived here with only a handful of servants and his three daughters for company. At times he talked of getting rid of the ‘wretched thing’ altogether, though Isobel knew that the idea grieved him terribly.

It had fallen to Grace to take on their mother’s role of managing the house. Anna helped her as best she could, given the burden of her affliction. To everyone’s surprise, the Major submitted happily to the new regime. Isobel was not so compliant. She thought Grace was a tyrant. A suspicious and jealous tyrant at that, at least where Isobel was concerned.

There was one positive in all this change. As the new mistresses of the house, Grace and Anna had been given their own rooms, leaving Isobel with this smaller front room all to herself. She cherished this refuge, even more now as she approached her seventeenth birthday. Here, late at night or first thing in the morning, she could sit quietly, writing her journal or sketching.

Isobel saw the first blush of orange on the horizon. She knew her father always consulted his Old Moore’s Almanac and she had done the same with her own copy in the morning room. Sunrise was due at 5.32 a.m. If only a bank of storm clouds like those in her nightmare would bring a downpour of rain her father might still be saved. But the ‘red sky’ of yesterday’s sunset had foretold the clear skies of this morning’s ‘shepherd’s delight’.

Father had chosen a fine day to die.

In the pre-dawn gloom, Isobel fumbled to light the lamp on her washstand. Her hands were trembling so violently it took her several attempts to perform this simple task. She then removed her night jacket and washed her face and hands. There was not a moment to lose. She listened carefully for the creak of her father’s door and his tread in the corridor. The servants would have started their chores downstairs by now but the house remained silent.

On a normal weekday morning Isobel would rise around nine, depending on how late she had danced or taken supper at a party the night before. She would ring for Sarah to bring muffins and hot chocolate or a tray of toast and tea. Father usually ate early in the breakfast room and was long gone by the time she and her sisters arose for their daily round of German, French, music, dance and drawing lessons.

But today was far from a normal day, Isobel reflected as she brushed her hair, trying to calm the terror that bubbled up in her breast with each vigorous stroke. Her face in the glass looked paler than usual, almost luminous, no doubt due to her night of tortured sleep but also exaggerated by the contrast of her charcoal black hair, which she tied up with ribbons in two plump wings just above her ears. She checked the precise middle parting that showed her scalp, as white and fragile as an egg.

Everything about her seemed fragile this morning, thought Isobel: her pale face, her leaden limbs, her aching chest. Unlike Grace, suffering did not improve Isobel’s looks. Where her sister’s features were sharpened and ennobled by sadness, hers merely looked pinched. Her own plainness relative to her sister’s haughty loveliness made Grace’s jealousy all the more difficult to understand. And to think they had once been so close as children.

She finished her toilette and took a deep breath. It was time to unlock the wardrobe. With every passing minute, the strangeness of this day engulfed her. The doors swung open and she stared at the bundle she had placed there late last night: her brother William’s spare trousers, shirt and jacket, all folded neatly beside a pair of leather riding boots and a cabbage-tree hat. They looked so outlandish here among her dresses and bonnets.

What on earth am I doing? She could not decide if her hastily made plans were brave or lunatic. Trespassing into secret male territory, the only way she could. disguised as a man. It outraged all decorum. She risked making a mockery of her family name. She risked her father’s scorn and fury. She might even be risking her own life. How could she possibly justify such madness? The answer was simple. To do nothing was worse. After all the ill fortune her family had suffered, Isobel was not prepared to stand by and let her father destroy himself. And destroy this little world she treasured. So she picked up her brother’s hat and thought about how to pin all her hair up inside it.

The previous evening, Sir Angus had invited Captain and Mrs Bradley, and Dr and Mrs Finch and their three daughters to dinner. The Bradleys and the Finches were old friends of the Macleods, going as far back as Sir Angus’s arrival in the colony nearly twenty-four years ago.

The Finches had come bearing a gift to entertain their hosts. Last week the long-awaited signal had gone up at Flagstaff Hill to let all of Sydney know that the mail ship was in. News from Home! An anxious crowd had formed at the dock and some poor postmen were even pursued on their rounds. The Finches had a bundle of letters from their eldest son, Aloysius, in London. He had dedicated many pages to his impressions of Prince Albert’s ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’, which had been opened by Her Majesty in May. Dr Finch shared several

passages describing the wonders of the Crystal Palace and its panoply of thirteen thousand exhibits from around the globe.

‘There were many remarkable innovations from Europe and the Americas,’ he read, ‘such as Mr Brady’s daguerreotypes, Mr Jacquard’s loom and Mr Colt’s revolvers. But visitors were left in little doubt that Britain was the undisputed leader in industrial technology and design. The building itself is a testament to British engineering and architectural genius.’

This patriotic observation was greeted with cheers. The Major proposed a toast to ‘Her Majesty, the Prince Consort and the Empire’ and the diners raised their glasses in unison. The young women at the table became even more animated when Dr Finch produced the novel souvenir his son had enclosed, called a ‘Lane’s Telescopic View’. Isobel thought it ingenious. Ten hand-coloured lithographic prints were cut out, pasted on board and arranged like a tableau, one behind the other, in a stiffened cloth tunnel. The whole device could be folded flat, concertina fashion, for mailing. To Isobel it resembled the toy theatres her brothers had played with as boys, staging the Battle of Waterloo in miniature.

Dr Finch set up the View on the sideboard and invited the Macleod girls to ‘take a peek’. Isobel went first. Through the peepshow lens she discovered a view stretching the full length of the Crystal Palace’s Great Hall. She laughed with delight. For a moment she could easily imagine herself as one of the guests strolling among the gushing fountains, the fully-grown trees and the giant showcases. ‘It’s as if you were actually there,’ she sighed.

For Isobel, London existed only in her imagination as a bright vision of order and splendour created by poets, painters and her parents’ memories. Like so many others, her father had come to New South Wales as a young man, with a wife and three children and plans for rapid advancement and easy wealth before escaping back home to England. despite these good intentions and several trips to the Old Country in the meantime on matters of business, Sir Angus had remained in the colony as its hard-working Surveyor-General. His beloved Winnie had reconciled herself to their term of exile but filled her daughters’ heads with nostalgic yearning. At least Alice had her prayers answered in the form of a rich husband with a townhouse in London and a manor in the country. There were times when Isobel also craved to be at the centre of the civilised world rather than here on its outer edge.

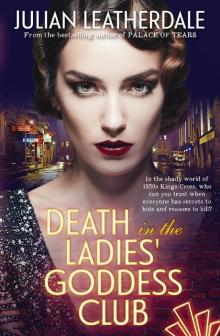

Death in the Ladies' Goddess Club

Death in the Ladies' Goddess Club The Opal Dragonfly

The Opal Dragonfly Palace of Tears

Palace of Tears